The Sunk Cost Fallacy: How to Protect Your Sports Betting Bankroll

It’s safe to assume that our significant losses hurt a lot more than we enjoy our wins. You might not know it, but this strong aversion to loss is a natural human tendency that most of us share.

When we let the fear associated with past losses affect our rational decision-making process, we fall victim to the ‘sunk cost fallacy’. Learning how the sunk cost fallacy affects sports betting and how to avoid it is essential for any aspiring “sharp.”

In this article, we equip you with the knowledge you’ll need to avoid the pitfalls of the sunk cost fallacy, and start maximizing the size of your bankroll.

What Is a Sunk Cost?

“Sunk cost” is a term that economists use for any paid cost that can’t be regained or reclaimed.

Think of someone buying a ticket to a hockey game. Somewhere between where she parked her car and the entrance, she lost her ticket. She searched everywhere, but couldn’t find the ticket. As a result, she was denied entry to the game. She can’t recover this cost, and her money is lost forever.

If someone owned a neighborhood grocery store, the lease payments on the physical space and advertising spend would be a sunk cost.

When we define “investment,” we don’t just mean that it’s purely economic. Investments can refer to money as well as time and emotions. Psychological stakes are just as significant as monetary investments when it comes to sunk costs.

What, Then, Is the Sunk Cost Fallacy?

The ‘sunk cost fallacy’ is when we let these irreversible investments (time, money, or otherwise) affect our rational decision making. We incorrectly (fallaciously) assign causality between our past, sunk cost investments, and our current decisions/investments.

Think back to the example of lease payments on a grocery store. If there is absolutely no way to turn a profit, the rational move would be to close the business. Yes, the owner would lose some money on the lease payments, but they’d lose less money by cutting their ties rather than keeping the business open.

If the owner decided to continue to throw money at the grocery store (because he’d already invested so much in the venture), they’d be guilty of the sunk cost fallacy. Past sunk costs should have no bearing on our future decisions.

Where Did the Sunk Cost Fallacy Come From?

If you’ve been reading the rest of our betting psychology series, you’re already familiar with Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, the two pioneers of the cognitive biases field, or what causes humans to make irrational decisions. Their groundbreaking work brought the sunk cost fallacy into the mainstream.

In their revolutionary study, they showed that humans tend to attach far greater value to losses than gains. In fact, the pain of losing is nearly two times stronger than the joys of winning.

Additionally, we don’t place nearly as much value as we think on our “well-being” or “wealth.” As humans, we’re much more concerned with winning and losing.

The more we’re invested in something, the stronger the effects of sunk cost fallacy.

The Origins of the Sunk Cost Fallacy Go Back Centuries

According to Kahneman and Tversky, feeling stronger about losses than wins can be traced back to our earliest evolutionary beginnings. Those roaming around in caves in prehistoric times were much more likely to survive if they prioritized not dying, instead of prioritizing achieving a goal, regardless of what it was.

Our ancestors ranked avoiding the ultimate loss (death) as higher than any gain. This tendency has obviously been passed down onto us. It might seem crazy that what our millennia-old ancestors did has a connection to our decision-making process, but the science stands up.

The Most Famous Example: The Concorde Fallacy

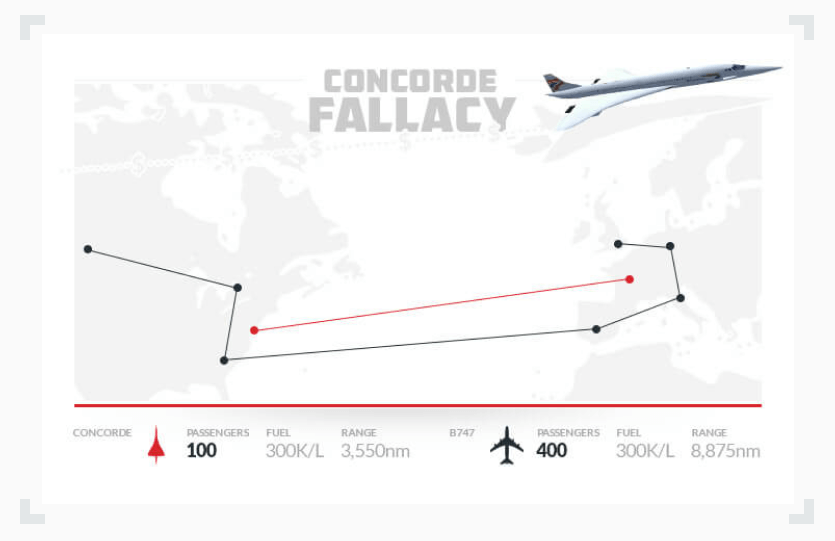

The Concorde was the world’s first supersonic passenger airline, able to fly at a top speed of over 1,300 mph. With the ability to fly from New York to London in a mere three and a half hours, the Concorde was the fastest commercial airplane ever made.

A single trip, however, was 30 times more expensive than a regular passenger jet, and the airplane had to be heavily subsidized by the British and French governments to stay in the air.

From the start, many people predicted that the Concorde was going to be an unmitigated financial disaster. Most didn’t see a reasonable way that the Concorde could ever become profitable, regardless of how impressive its aviation abilities were. Between fuel and maintenance costs, the Concorde was sunk from the outset.

From the high-ups at Air France and British Airways to the UK and French government representatives, few wanted to give up on the Concorde. The psychological and financial investments in the airline these parties had made were so great that the Concorde airline persevered against better judgment.

Eventually, the Concorde was permanently grounded in 2003. It remains one of the biggest disasters in the history of aviation, continued only because of the sunk cost fallacy.

Real Life Examples of the Sunk Cost Fallacy

Sunk cost fallacy is more prevalent than the average person imagines. Loss aversion is a dominant force is all of our lives, and the desire to avoid losing often causes us to do very odd things.

- A patron goes to an all-you-can-eat BBQ restaurant, only to discover he’s still quite full from lunch and not in the mood to stuff himself with as much food as he can. However, he’s already made the trip to the restaurant, which is 45 minutes across town, and paid the $25 flat fee. Not wanting to waste his money and time invested, he eats until he’s sick and is forced to miss work the next day. The desire to avoid wasting his investment of time and money causes him to lose the entire next day.

- A couple goes to a movie theatre to see the latest horror film, only to come to a mutual realization, 30 minutes in, that it’s the worst film either of them has ever seen. Instead of leaving and doing something else they would find enjoyable, they persevere through the rest of the movie. They don’t want to waste the $12 they spent on the movie ticket, even though they know they’ll find the remaining 90 minutes unpleasant.

- A graduate student is halfway through her PhD in chemistry when she figures out a brilliant idea for a company. She consults with her peers, and everyone believes that her idea is astoundingly brilliant. They recommend that she drop out to pursue her idea fully. However, since she’s invested so much time in not only her degree, she decides to complete her PhD. By the time she receives her doctorate, someone else has acted upon her brilliant idea.

- An NHL general manager invests $36 million over six years in an aging veteran right winger, believing that he’ll regain his form well into his 30s. Within the first two years of the contract, the player struggles to put up double-digit goal totals, barely eclipsing 20 points. Instead of trading him to a team that needs to reach the salary cap floor, the general manager decides to hold onto this player because he’s already invested so much in him.

Never Chase Losses: The Sunk Cost Fallacy and Sports Betting

In our guide to managing your bankroll like a professional bettor, we talk about the importance of staying disciplined when it comes to wagering size.

Under no circumstances would we ever recommend that a bettor increase their unit size to make up for lost bets. Bettors who commit this are classic victims of the sunk cost fallacy.

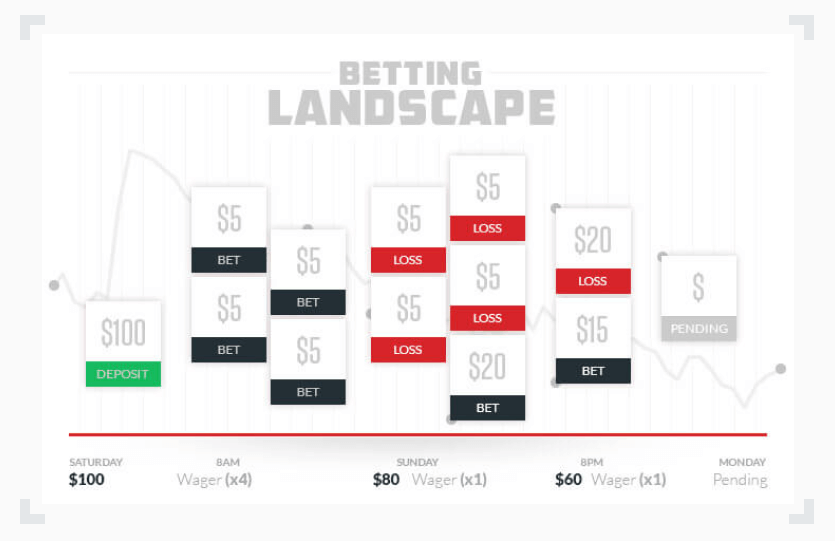

Say, hypothetically, that a bettor has spent his Sunday betting against the spread in the NFL. This bettor wagered $5 on four separate games and lost every single bet. As a result, he lost $20, and his bankroll is reduced from $100 on Sunday morning to $80 on Sunday night.

Wanting to recoup his losses after a disastrous Sunday, the bettor wagers $20 on Monday night’s game.

If the bettor had lost his Monday night wager, it would mean that his bankroll would have been obliterated to $60. This would equate to an utterly disastrous 40% reduction in his bankroll in a mere 36 hours.

A sharp wouldn’t fall victim to the sunk cost fallacy here, and would instead continue to make conservative, measured bets at a reasonable bet size.

Act Like a Sharp

Chasing losses like the bettor in our hypothetical example isn’t smart, prudent, or professional. However, it’s all too common. Acting irrationally usually ends up coming back to bite us in the rear end, and discipline is essential for long-term success in sports betting.

Losing bettors should strive to avoid cognitive biases and recalibrate their use of sharp strategy.

Use the Sunk Cost Fallacy to Increase Betting Win Percentages

The sunk cost fallacy helps us understand that the human mind loves to play tricks on us (We’re hardwired to hate losing!). Recognizing this will help you analyze your bets rationally, and prevent you from wasting money on risky wagers just to win your losses back.

To avoid falling into any other psychological traps that frequently affect bettors, check out the rest of our betting psychology series.

Evergreen Writer/Editor; Sportsbook Expert

With nearly two decades of experience in sports media, Paul Costanzo turned his professional attention to sports betting and online gambling in January of 2022. He's covered every angle of the industry since then, managing and creating content for PlayMichigan and The Sporting News, and now SBD.